Living in the XIX th. Dynasty (c. 1295-1255 B.C.), her full name was Nefertari Merytmut, meaning “Beautiful Companion, Beloved of Mut”. She was the Great Royal Wife of Ramesses II the Great, one of the best known of the Egyptian queens, next to Cleopatra, Nefertiti and Hatshepsut. Her tomb, QV66, is the largest, most lavishly decorated and spectacular in the Valley of the Queens. Ramesses II also constructed for her a temple at Abu Simbel, next to his own colossal monument. He even made the size of her statues, on its façade, to the same scale as his own.

Tomb of Queen Nefertari – Valley of the Queens – Luxor, Egypt

Nefertari’s origins

Nefertari’s origins are unknown, but discoveries in her tomb, which include a cartouche of the Pharaoh Ay (found on a what was either a pommel of a cane or a knob from a chest), suggest she may have been related to rulers of the 18th Dynasty, included Tutankhamun, Nefertiti, Akhenaten and Ay. She married Ramesses at age of thirteen, who was himself only fifteen, before he became a pharaoh. She was the most important of his eight wives for at least the following twenty years. She died sometime during the 25th regnal year of the reign of Ramesses and the reason for her death remains uncertain.

Although she had at least four sons and two daughters, none of these succeeded to the throne. The heir to the throne of Ramesses II was Prince Merneptah, his 13th son by another wife, Isetnofret.

Discovery and Location of the tomb

Discovered by Ernesto Schiaparelli in 1904, the tomb of Nefertari (QV66) is situated at the bottom of the north side of the main wadi in the Valley of the Queens.

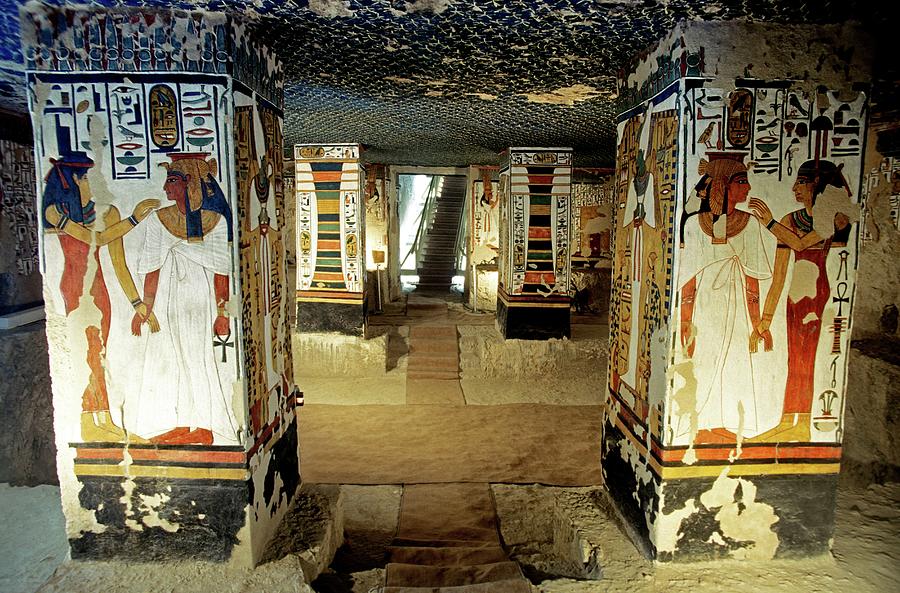

The limestone in the Theban area is not of very high quality and it is fractured by earthquakes; it also has bands of flint. All of this means that several layers of plaster were required to be applied to the walls before painting.

Because of the many serious problems, which affected its beautifully painted walls, the tomb was closed to the public in the 1950’s. Repairs had been carried out to try to stabilize the serious cracks in the plaster, of which large areas had completely broken away. But it wasn’t until 1986 that the first serious modern work was carried out in order to stabilize the paintings, which was undertaken by the Getty Conservation Institute of America. Later, in February 1988, a full restoration started, preceded by various studies carried out by an international team of scientists.

It was found that the main culprit for the damage was not ancient tomb robbers, but nature itself. Even here it was not earthquakes but salt which caused the problem. The local limestone contains salt, as did the mud from the Nile, used to make the plaster. The seepage of water through the rock had created crystals, which had caused the plaster to crack and the paint to flake. These crystals, which can grow extremely large, often to centimeters in size, have forced large areas of plaster from the walls, many of which it was impossible to restore. Even since the time of Schiaperelli’s photography of the tomb, the effect of the destruction has been progressive, as best seen in a comparison of the condition after the recent conservation and a black and white photo taken by Schiaparelli.

What Remained

The remains of the pink granite lid found by Schiaparelli are in the Turin Museum.

The sarcophagus was oblong. As usual with royal sarcophaguses of the 18th Dynasty, it combined both images and texts. These texts are produced in longitudinal and transverse bands, imitating a mummy fastening.

On top of the lid, level with her face, can be recognized the goddess Nut, with expanded wings, kneeling on the hieroglyphic sign for gold.

The supplication of Nefertari is addressed to the great goddess.

Regarding the mummy: Schiaparelli only found part of the two knees in the funeral chamber, among shreds of material coming from the mummification.

This was a very sad end for “the most beautiful of all”.

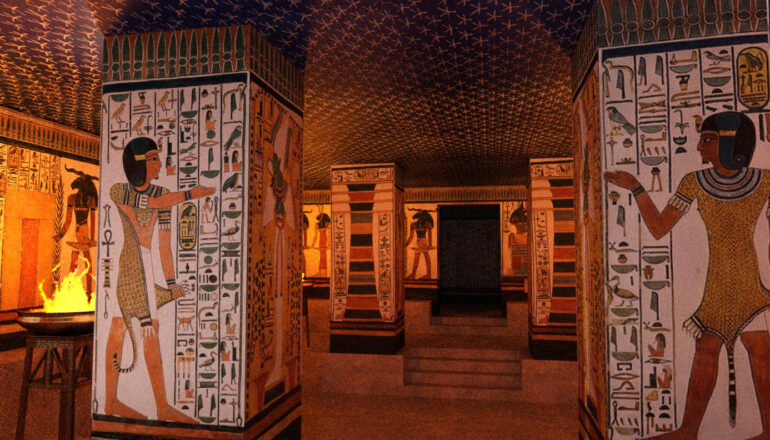

About the Decoration of the Tomb

This tomb represents a life-size copy of the Book of the Dead, in stone. A copy of the book, on a papyrus roll, was placed even in the tombs of nobles, scribes and craftsmen. Some of these were extremely long, the well-known Papyrus of Ani (a scribe) being approx. 23 meters in length. In Nefertari’s tomb the walls have been substituted for the papyrus, its painted scenes being the vignettes.

Two other beautiful examples of the Book of the Dead exist on this site. One of which is a copy of the mysterious prince Maiherkhepri, dating in the days of Thutmosis IV, which was recovered with the character’s intact mummy in a tomb of the Valley of the Kings, KV36.

The tomb and its decoration are of an exceptionally high quality, with almost every surface being decorated in vibrant colors. It would be produced by workmen responsible for the Valley of the Kings, from the village of Deir el-Medina. Although Nefertari died sometime during the 25th regnal year of the reign of Ramesses, all the evidence shows that her tomb was finished in time for her burial.

The ceilings throughout are painted deep blue and decorated with yellow stars. The exception being the soffit (ceiling) of the entrance doorway to the first chamber, at the bottom of the entry stairs.

The walls contain no images taken from her daily life, but consist of a journey through the underworld, to be united eternally with Osiris. The journey then continues outwards, to the doorway at the foot of the stairs leading to the upper world. Here the queen emerges from the eastern horizon reborn in the likeness of a solar disc (see d1-soffit), to immortalize forever her victory over the world of darkness.

Because Nefertari wasn’t a pharaoh and because there were no scenes of daily life, the choice of texts used on the walls was somewhat restricted. The ones finally chosen, either by the architects, the priests or perhaps Ramesses himself, were taken from the “Book of the Dead”.