About the schools of the ancient Egyptians, Romans, Greeks…

let’s find out together how education was organized in the Mediterranean civilizations that preceded us.

The first schools were born in Mesopotamia, where the invention of writing, around the 4th millennium BC, had made its teaching inevitable and necessary: Sumere schools, called edubba (i.e. tablet houses), then arose near temples and palaces, with the aim of forming the scribes who would take care of the public administration.

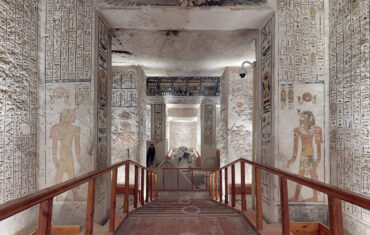

Homes of Life. The same happened a few centuries later in Egypt. “Even in Egyptian civilization, the main role of the school was to prepare children to enter bureaucracy,” explains historian David Silverman in his essay Ancient Egypt (Mondadori, 1998): “Some were educated in the Pharaoh’s palace, but most studied at home or in schools, called Houses of Life.” Under the supervision of strict masters, from the age of 5-6 and up to 15-16, would-be scribes imprisoned by composing hieroglyphics and writing in hieratic (similar to our italics) on crock tablets.

Textbooks. There was even a kind of subsidiary, called Kemit, rich in formulas useful to write letters, funeral texts, and religious hymns. However, education was reserved for males (apart from rare exceptions, females were home-schooled), while poorer children worked in shops or fields.

Many centuries later, it was the Greeks who introduced the term scholé to indicate “any activity unrelated to the response to practical needs”, as the study considered. Depending on the polis in which they were born, however, things changed a lot: in Sparta, the state took into custody the children from 7 to 18 years old and subjected them to a very hard military training(agoghé), which also included the teaching of writing and reading. And a similar upbringing, but more focused on physical activity, was also planned for girls.

Scholé. In Athens (as almost everywhere at the time), however, females were excluded from any form of education that was not related to domestic activities, while the elementary education of the males was entrusted to three different teachers, where the children of the good family went with a slave called pedagogue (accompanying children). The morning began with the grammarian, who taught them to read, write, account for, and memorize poems.

They learned to play the lyre, and they did gymnastics. As adults, young people could attend the Schools of Philosophy and Rhetoric. These were so prestigious that their fame continued even in the Roman world, where the richest children, often educated by preceptors of Hellenic origin, went to Greece to perfect their education.

The less fortunate Roman children, from 7 to 12 years old, were instead entrusted to the edicts, who inculcated them “the basics” to the sound of legumes, giving lessons in porches or public squares. The pupils, equipped with wax or wooden tablets were also here mostly male. The most advanced stage of education, after the age of 12, involved the intervention of the Grammaticus and the author, with which they deepened grammar, literature, and rhetoric.