Many world-famous museums have expositions dedicated to Ancient Egypt. But none of them can boast of such a huge and diverse collection as the Cairo Museum. More than 150,000 exhibits are stored within the walls of this repository. Antiquities lovers from all over the world come to Cairo to see artifacts that were created thousands of years ago.

A new Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) will be opened in 2020. It is being built in Giza, not far from the famous pyramids. They plan to move half of the exhibits there. Judging by the photos of the new Museum that appear in the press, it will be a modern building built using the latest technologies. We will take a closer look at the old Cairo Museum, which has been storing the largest collection of historical artifacts of the ancient Egyptian civilization for more than 100 years.

History of the Cairo Museum

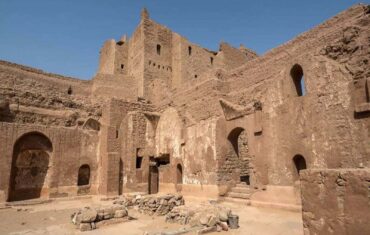

For a long time, the Egyptian authorities did not show much interest in the archaeological values found in the country. Ancient tombs were ruined by treasure seekers, and objects that they considered to be of no value were simply thrown away. The rest was sold to Europeans. Archaeological expeditions, mostly European and American, took all the finds out of Egypt, and no one was particularly interested.

In 1835, the first Museum was founded in Cairo. It was then that Mohammed Ali, the ruler of Egypt, banned the export of historical values from the country. A special body, the Commission for valuables accounting, was created.

It is interesting. The first Museum was open until 1855. Egyptian ruler Abbas Pasha presented all the Museum’s exhibits to Archduke Maximilian of Austria. Today they can be seen in the Historical Museum of Vienna. The ruler of Egypt treated the Museum as property. If he wants he can sell or give it away.

The Museum of Bulak

In 1858 Auguste Mariette, a French Egyptologist, created a new Department of antiquities and started a new collection.

The first collection consisted of items found by Mariet himself. The new Museum was given a building that stood on the Bank of the Nile, and Mariet was appointed Director. In 1878, the Museum of Bulaque suffered because of the Nile River flood. Some of the exhibits were damaged. After 3 years, for the same reason, the collection was forced to evacuate. The valuables were moved to the former Royal residence, where they were stored until 1902.

In 1902, they completed the construction of a new Museum, which is known around the world as the Cairo Egyptian Museum.

The first floor of the Egyptian Museum

The exposition is organized in more or less chronological order, so heading clockwise from the entrance through the outer galleries, you will pass through the Ancient, Middle, and the New Kingdom, and finish the tour with the Late and Greco-Roman periods in the East wing. This is the correct approach from the point of view of history and art criticism.

An easier way to explore is to walk through the atrium, which spans the entire era of the Pharaonic civilization, to the beautiful hall of the Amarna era in the North wing, and then return and walk through the departments that you are most interested in, or go up to the second floor for an exhibition dedicated to Tutankhamun.

In order to cover both options, the article divides the lower floor into six sections:

- The Atrium

- The Ancient Kingdom

- The Middle Kingdom

- The New Kingdom

- The hall of the Amarna era

- The East wing.

Whatever route you choose, it is worth starting from The atrium foyer (hall 43), where the story of the Pharaonic dynasties begins.

The rotunda and Atrium

In the Rotunda, located inside the Museum lobby, there are monumental sculptures of various eras, in particular, standing at the corners of three colossi of Ramesses II (XIX dynasty) and a statue of Amenhotep, the son of the Royal architect Hapu, who lived during the reign of the XVIII dynasty. Here, in the Northwest corner, are sixteen small wooden and stone statues of an official of the XXIV century BC named IBU, depicting him at various periods of his life.

To the left of the door is a limestone statue of the seated Pharaoh Djoser (#106), installed in the serdaba of his step pyramid in Saqqara in the XXVII century BC and removed by archaeologists 4,600 years later. Those who consider the reign of Djoser to be the beginning of the age of the Ancient Kingdom refer to the preceding period as early Dynastic or Archaic.

The real beginning of dynastic rule is immortalized on the famous exhibit located in hall 43, at the entrance to the atrium. The Narmer pallet (a decorative version of a flat tile that was used to rub paint) depicts the Union of two kingdoms (about 3100 BC) by a ruler named Narmer or Menes. On one side of the monument, the ruler in the white crown of Upper Egypt strikes the enemy with a Mace, while the Falcon (Horus) holds another prisoner and tramples with its feet the papyrus, heraldic symbol of Lower Egypt.

The reverse side shows the ruler in a red crown examining the bodies of the slain, as well as destroying the fortress in the form of a bull. The two tiers of images are separated by figures of mythical animals with entwined necks, which are kept from fighting by bearded men, a symbol of the political achievements of the ruler. Along the sidewalls of the hall are two funeral boats from the pyramid in Dashur (Senusert VIII-XII dynasty).

Going down to hall 33, which is the atrium of the Museum, you will see the pyramidions (keystones of the pyramids) from Dashur and sarcophagi of The new Kingdom era. Overshadowing the sarcophagi of Thutmose I and Queen Hatshepsut (Dating from before she became a Pharaoh) is the sarcophagus of Merneptah (#213), surmounted by a figure of the Pharaoh himself in the form of Osiris and decorated with a relief image of the sky goddess Nut, who protects the ruler with her arms. But Merneptah’s desire for immortality was not realized. When the sarcophagus was discovered in Tanis in 1939, it contained the coffin of Psusennes, ruler of the twenty-first dynasty, whose gold-covered mummy is now displayed on the upper floor.

In the center of the Atrium is a fragment of the painted floor from the Royal Palace in tel El-Amarna (XVIII dynasty). Cows and other animals roam along the reedy banks of the river, which is teeming with fish and water birds. This is a fine example of the lyrical naturalism of the art of the Amarna period. To learn more about this revolutionary era in the history of the pharaohs, head up past the imperturbable colossi of Amenhotep III, Queen TI, and their three daughters, the predecessors of Akhetaten and Nefertiti, whose images are located in the North wing.

But first, you must pass through hall # 13, which (on the right) houses the victory stele of Merneptah, also known as the stele of Israel. Its name is derived from a phrase from the story of the conquests of Merneptah – ” Israel is desolate, its seed is gone.” This is the only known mention of Israel in the texts of Ancient Egypt.

This is why many believe that the Exodus took place during the reign of Merneptah, son of Ramesses II (XIX dynasty), although this view has been increasingly criticized recently. On the other side is an earlier inscription that tells of the deeds of Amenhotep III (Akhenaten’s father), performed in praise of the God Amun, whom his son later rejected. At the other end of the hall is a model of a typical Egyptian house from the excavations of Tell El-Amarna, the short-lived capital of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, who are privileged to have their own separate exhibition in halls 8 and 3, a little further on.

- Halls of the Ancient Kingdom

The southwest corner of the first floor is dedicated to the Ancient Kingdom (about 2700-2181 BC) when the pharaohs of the third and sixth dynasties ruled Egypt from Memphis and built their pyramids. Along the Central wing of halls 46-47, there are funerary statues of important nobles and their servants (the custom of burying servants together with their master ceased with the end of the second dynasty). The relief from the temple of Userkaf (hall # 47, on the Northside of the entrance to hall # 48) is the first known example of the depiction of nature paintings in the decor of Royal funerary structures. The figures of the variegated Kingfisher, the purple Reed Warbler, and the sacred IBIS are clearly distinguishable.

Along the North wall of hall 47 are displayed six wooden panels from the tomb of Hesi-Ra with images of this senior scribe of the pharaohs of the third dynasty, who is also the earliest known dentist. In hall 47, there are also ushabti – figurines of workers who are depicted preparing food (Nos. 52 and 53). Here, too, are the three slate sculpture triads of Menkaura from his valley temple in Giza, originating from the temple in Giza: the Pharaoh is depicted next to Hathor and the goddess of the Aphroditopolian nome. A pair of alabaster slabs depicting lions at the fourth pillar on the Northside may have been used for offerings or libations at the end of the second dynasty.

Among the most impressive exhibits in hall 46 are the statuettes of Khnum-Hotep, the Keeper of the Royal wardrobe, a man with a deformed head, and a hunched back who apparently suffered from Pott’s disease (Nos. 54 and 65). Fragments of the Sphinx’s beard are located at the end of the lobby (hall # 51), on the left under the stairs (#6031). The beard probably had a length of 5 meters before it was broken into pieces by Mamluk troops and soldiers of Napoleon during shooting practice. In addition, in hall No. 51 there is a sculptural head of the Pharaoh of the V dynasty of Userkaf (No. 6051), which is the earliest known at the moment statue size larger than natural.

At the entrance to hall 41, reliefs from the V-dynasty tomb in Meydum (No. 25) depict hunting in the desert and various types of agricultural work. On another slab (No. 59) from the fifth dynasty tomb at Saqqara, we see the weighing, threshing, and sorting of grain, the work of a glassblower, and a statue Carver. The women depicted in these reliefs are dressed in long dresses, men – in loincloths, and sometimes without clothes at all (you can see that the rite of circumcision was one of the Egyptian customs). Hall # 42 boasts a magnificent statue of Chephren, his head crowned with the image of the Horus (# 37).

The statue, brought from the valley temple of Chephren in Giza, is carved from black diorite, and white marble flecks successfully emphasize the muscles of the legs and clenched fist of the Pharaoh. Equally impressive is the left-hand wooden statue of Kaaper (#40), a plump, thoughtful – looking figure that the Arabs who worked at the Saqqara site called “Sheikh al-Balad” because he looked like their village chief. One of the two recently restored wooden statues on the right (# 123 and # 124) probably depicts the same person. We should also note the remarkable statue of a scribe (No. 43) spreading a papyrus scroll on his lap.

On the walls of hall 31, there are reliefs made on Sandstone found in Wadi Maghara on the Sinai Peninsula, near the ancient turquoise mining sites. Paired limestone statues of Ra-Nofer symbolize his dual status as high priest of the god Ptah and the God Sokar in Memphis. The statues look almost identical, differing only in their wigs and loincloths, both of which were created in the Royal workshops, possibly by the same sculptor.

Room 32 is dominated by life-size statues of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nefert from their mastaba in Meydum (IV dynasty). The Prince’s skin is painted brick-red, and his wife’s is cream-yellow, a distinction common in Egyptian art. Nefert is dressed in a wig and tiara, her shoulders are wrapped in a transparent veil. The Prince wears a simple loincloth wrapped around his waist. Please note the live image of the dwarf Seneb and his family (#39) on the left.

The face of the Keeper of the Royal wardrobe, who is embraced by his wife, looks peaceful; their naked children put their fingers to their lips. In the second niche on the left side hangs a bright and lively example of wall paintings, known as “Meydum geese” (III-IV dynasties). The heyday of the Ancient Kingdom is represented only by the statue of Ti on the left (No. 49), the period of decline of this era is much richer in monuments: immediately next to the entrance are the oldest known metal sculptures (about 2300 BC) – statues of Pepi I and his son.

The Queen Hetepheres ‘ furniture displayed in hall 37 was restored from a pile of gold and pieces of rotten wood. Hetepheres, the wife of snefru and mother of Cheops, was buried near the pyramid of her son at Giza; a bier, Golden vessels, and a four – poster were placed with Her in the tomb. In addition, in the same hall, in a separate window, there is a tiny statue of Cheops, the only known portrait image of the Pharaoh – the Builder of the great pyramid.

- Halls of the Middle Kingdom

In hall 26, you enter the Middle Kingdom, when centralized power was established under the rule of the XII dynasty and pyramid construction resumed (around 1991-1786 BC). A dark relic of the previous era of internal troubles (which ended the First transition period) is located on the right. This is a statue of Mentuhotep Nebhepetra with huge feet (a symbol of power), a black body, arms crossed on the chest and a curly beard (features characteristic of images of Osiris).

In ancient times, it was hidden in an underground chamber near the memorial temple of Mentuhotep in Deir El-Bahri and later accidentally discovered by Howard Carter, whose horse fell through the roof. On the opposite side of the hall stands the sarcophagus of Dagi (#34). If the owner’s mummy was still inside, it could have used a pair of “eyes” painted on the inside of the coffin to look at the statues of Queen Nofret standing at the entrance to hall 21 in a tight dress and wig of the goddess Hathor.

The statuettes in the back of hall 22 are striking with the atypical vivacity of their faces, contrasting with the maniacal frozen stare of the wooden statue of Nakhti on the right. The hall also displays portraits of amenemhat III and Senusert I, but first of all, you will be drawn to the burial chamber of HorHetep of Deir El-Bahri in the middle of the hall, which is covered inside with picturesque scenes, spells and texts.

Around the camera are ten limestone statues of Senusert III recovered from his pyramid complex in Liste. Compared to the statue of the same Pharaoh, made of cedar wood and standing in the window to your right (#88), these sculptures are very formal. The thrones of these statues depict different versions of the symbol of unity of Sematawi: Hapi, the God of the Nile, or Hor and Set with intertwined plant stems-symbols of Both lands.

The main idea of Egyptian statehood is expressed by the unique double statue of Amenemhat III (#508) in hall # 16. Paired figures-personifications of the Nile deity offering his people fish on trays-can symbolize the Upper and LowerEgypt or the Pharaoh himself and his divine essence ka. When you leave the halls of the Middle Kingdom, five sphinxes with lion heads and human faces stand to your left and stare after you. The era of anarchy – the Second transitional period and the Hyksos invasion-are not represented in the exhibition.

- Halls of the New Kingdom

Moving to hall 11, you enter a New Kingdom-the era of the revival of the power of the pharaohs and the expansion of the Empire during the XVIII and XIX dynasties (about 1567-1200 BC). Uniting Africa and Asia, the Egyptian Empire was created by Thutmose III, who had to wait a long time for his turn, until his very non-warlike stepmother, Hatshepsut, ruled as Pharaoh. In the Museum there is a column from her great temple in Deir El-Bahri: from above, the sculptured head of Hatshepsut, crowned with a crown (#94), looks imperiously at visitors. On the left side of the hall is an unusual statue of ka Pharaoh Hora (#75), mounted on a sloping base, symbolizing his posthumous wanderings.

In hall 12, you will see a statue of Thutmose III (#62) made of slate slate, as well as other masterpieces of art from the XVIII dynasty. In the back of the hall, in the sacred ark from the destroyed temple of Thutmose III in Deir El-Bahri, there is a statue of the goddess Hathor in the form of a cow emerging from a thicket of papyrus. Thutmose himself is depicted in front of the statue, under the head of the goddess, and also in a fresco on the side, where he sucks milk like an infant. To the right of the ark is a stone statue of the vizier Hatshepsut Senenmut (#418) with the daughter of Queen Nefr-Nefero, in the second niche on the right – a smaller statue of the same couple.

The relationship between the Queen, her daughter and the vizier is the subject of many speculations. A fragment of a relief from Deir al-Bahri (second niche on the left) depicting an expedition to punt belongs to the same period. It shows the Queen of Punta suffering from elephantiasis and her donkey, as well as Queen Hatshepsut watching them during a trip to this fairyland.

To the right of the relief is a statue of the God Khonso made of gray granite with a lock of hair symbolizing youth, and the face (as it is commonly believed) of the boy Pharaoh Tutankhamun. It was taken from the temple of the moon God in Karnak. On either side of this sculpture and the “Punt relief” are two statues of a man named Amenhotep, representing him as a young scribe of low birth and an eighty-year-old priest who was honored for overseeing a large-scale construction similar to that of the Colossi of Memnon.

Before turning the corner to the North wing, you will see two statues of the lion-headed Sekhmet found in Karnak. Hall 6 is dominated by the Royal sphinxes with the heads of Hatshepsut and her family members. Some of the reliefs on the southern wall come from the Maya tomb at Saqqara. The tomb was discovered in the nineteenth century, then lost and found again in 1986. Hall 8 is largely an addition to the hall of the Amarna era, it also houses a monumental double statue of Amun and Mut, broken into pieces by medieval stonemasons and lovingly collected from fragments that have long been lying in the basement of the Museum in Karnak, where the monument originally stood. Those parts that could not be inserted into the puzzle are displayed in a stand behind the sculpture.

To the left of the stairs in hall 10, note the colored relief on a slab from the temple of Ramesses II in Memphis (#769), which depicts the king bringing the enemies of Egypt to submission. In a motif repeated on dozens of temple pylons, the king holds a Libyan, a Nubian, and a Syrian by the hair and swings an axe. The pharaohs of the Ramessid dynasty, who had never fought themselves, were particularly fond of such reliefs.

The hall ends with an artistic rebus (#6245): the statue of Ramesses II depicts the king as a child with a finger to his lips and a plant in his hand, protected by the Sun God RA. The name of God in combination with the words “child” (month) and “plant” (su) forms the name of the Pharaoh. From hall 10, you can continue exploring the New Kingdom in the East wing or take the stairs to the Tutankhamun gallery on the next floor.

- The hall of the Amarna age

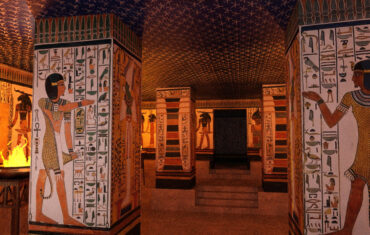

Hall 3 and most of the adjacent hall 8 are dedicated to the Amarna period: an era of a break with centuries-old traditions, which lasted for some time after the end of the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten (about 1379-1362 BC) and Queen Nefertiti. Rejecting Amun and the other Theban gods, they proclaimed the cult of a single God-Aten, built a new capital at tel-El-Amarna in Middle Egypt to rid themselves of the old bureaucracy and left behind mysterious works of art.

From the walls of hall 3, four colossal statues of Akhenaten look down at you. Their elongated heads and faces, their full lips and flared nostrils, their rounded thighs and bellies suggest a hermaphrodite or a primeval earth goddess. Since the same features are also present in the images of his wife and children on certain stelae (in the left niche and in the Windows opposite) and in tomb reliefs, there is a theory that the artistic style of the Amarna epoch reflects some physical anomaly of Akhenaten (or members of the Royal family), and the inscriptions hint at some perversion.

Opponents of this hypothesis object: the head of Nefertiti, stored in Berlin, proves that this was only a stylistic device. Another feature of Amarna art was the expressed interest in private life: a stele depicting the Royal family (# 167 in hall # 8) depicts Akhenaten holding his eldest daughter Merit-Aton in his arms, while Nefertiti cradles her sisters. For the first time in Egyptian art, for example, the Breakfast scene appears. The masters of the Amarna age focused their attention on the earthly world, rather than on the traditional themes of the afterlife.

The art is filled with new vitality – note the loose brushstrokes on the fragments of the frescoes from scenes in the swamp represented on the walls of room # 3. To the left of the entrance to the hall window “And” exhibited some of the documents in the Amarna archive (the rest are in London and Berlin). They include requests to send troops to help the Pharaoh’s supporters in Palestine, the aftermath of his death, and Nefertiti’s search for allies to fight those who encouraged Tutankhamun to turn the Amarna revolution around. These cuneiform tablets were kept in baked clay “envelopes” in the archives of the Amarna diplomatic office.

Akhnaton’s coffin with inlaid carnelian, gold and glass can be seen in hall 8, its lid is displayed next to the gold lining of the lower part. These treasures disappeared from the Museum between 1915 and 1931, but were discovered in Switzerland in 1980. Now the gold decoration has been restored and placed on a plexiglass model that has the assumed shape of the original coffin.

- East wing

An incentive to move further from the halls of the New Kingdom to the East wing may be the statue of the wife of Nakht Mina (#71), located in hall 15, which looks very sexy. In hall 14, there is a huge alabaster statue of SETI I, whose sensuous modeling of the face evokes the bust of Nefertiti.

It is likely that the Pharaoh was originally depicted in a Nemes-a headdress that we can see on the funeral mask of Tutankhamun. Even more impressive is the restored triple statue of pink granite, depicting Ramesses III, who is crowned by a Chorus and Set, embodying respectively order and chaos.

The new Kingdom gradually declined during the reign of the XX dynasty and died under the XXI dynasty. It was followed by the so-called Late period, when foreign rulers were mostly in power. At this time, the statue of Amenirdis the elder, which the Pharaoh placed at the head of the Theban priestesses of Amun, was displayed in the center of hall 30.

On the head of Amenirdis, dressed as the Queen of the New Kingdom, is a Falcon’s headdress, decorated with a uraeus, which was once crowned by the crown of Hathor with a sun disk and horns. The most memorable of the numerous statues of gods in hall 24 is the image of a pregnant female hippopotamus-the goddess of childbirth, Taurt (or Toerit).

Halls 34 and 35 highlight the Greco-Roman period (from 332 BC), when the principles of classical art began to actively penetrate the symbolism of Ancient Egypt. The fusion of styles characteristic of the era is demonstrated by the bizarre statues and sarcophagi in hall 49. Hall 44 is used for temporary exhibitions.

Second floor of the Egyptian Museum

The most significant part of the exposition on the second floor is the halls with the treasures of Tutankhamun, which occupy the best areas. After viewing these objects, everything but the mummies and a few masterpieces seems dim, although in other rooms there are artifacts as good as those displayed below. For their inspection, come to the Museum on some other day.

Halls Of Tutankhamun

The set of burial utensils of the Pharaoh-boy Tutankhamun includes 1,700 items that fill a dozen halls. Given the shortness of his reign (1361-1352 BC) and the small size of his tomb in the Valley of the Kings, the priceless treasures that seem to have belonged to at least such great pharaohs as Ramesses and SETI are even more striking.

Tutankhamun simply sided with the Theban counter-revolution, which destroyed the Amarna culture and restored the former power of the cult of Amun and its priests. However, the influence of Amarna is evident in some of the exhibits, which are arranged in much the same way as they were in the tomb: chests and statues (hall 45) in front of the furniture (halls № 40, 35, 30, 25,15, 10), ARKS (halls 9-7) and gold items (hall 3).

Next to them are ornaments (hall 4) and other treasures from various tombs (halls 2 and 13). Most of the visitors rush to the last four rooms (rooms 2, 3, and 4 close fifteen minutes earlier than the others), ignoring the sequence just indicated. If you are one of these users, skip the detailed description below.

When members of the Howard Carter expedition in 1922 broke into the sealed passage of the tomb, they found the front chamber literally filled with caskets and fragments of things left by robbers. There were also two life-size statues of ka Tutankhamun (standing at the entrance to hall 45), whose black skin color symbolizes the rebirth of the king. Immediately behind them are Golden statues of Tutankhamun, depicting him hunting with a harpoon.

In hall 35, the main exhibit is a gilded throne with handles in the form of winged serpents and legs in the form of animal paws (# 179). On the back is a picture of a Royal couple resting in the rays of the sun-Aten. The names of the spouses are given in the form adopted for the Amarna era, which allows us to attribute the throne to the period when Tutankhamun still adhered to the sun-worshiping cult.

Other mundane items that the boy Pharaoh took with him to the otherworld include a set made of ebony and ivory for a Senet game similar to our draughts (#49). A lot of ushibti figurines were supposed to perform tasks that the gods could give to the Pharaoh in the other world (on the sides of the entrance to hall # 34).

In hall # 30 there is a casket with “prisoners ‘ Staffs” (#187), the images on which, inlaid with ebony and ivory, symbolize the unity of the North and South. The bust of the Pharaoh-a boy born from a Lotus (#118), testifies to the continued influence of the Amarna style during the reign of Tutankhamun. The ceremonial throne (#181) in hall # 25 is the prototype of the Episcopal chairs in the Christian Church. Its back is decorated with a luxurious inlay of black wood and gold, but it looks uncomfortable. More typical for the time of the pharaohs is a wooden chair and footstools, as well as an ornate chest of drawers.

The king’s clothes and ointments were stored in two magnificent chests. On the lid and side walls of the “Painted chest” (#186) in hall # 20, he is depicted hunting ostriches and antelopes or destroying the Syrian army from his war chariot, shown larger than life size. The end panels show the Pharaoh in the form of a Sphinx, trampling down his enemies.

Unlike the warlike images of Tutankhamun on other objects, the scene on the lid of the “Inlaid chest” is made in the Amarna style: Ankhesenamun (daughter of Nefertiti and Akhenaten) presents a Lotus, papyrus and Mandrake to her spouse surrounded by blooming poppies, pomegranates and cornflowers. The Golden ark, decorated with idyllic scenes of family life, once contained statues of Tutankhamun and his wife Ankhesenamon, which were stolen in antiquity.

From the ivory headrests in hall 15, it is entirely logical to move on to the gilded boxes dedicated to the gods, whose animal images are carved on the pillars (Nos. 183, 221 and 732 in hall 10). In the next hall No. 9 is the sacred ark of Anubis (No. 54), which was carried before the funeral procession of the Pharaoh: the protector of the dead is depicted as a vigilant Jackal with gilded ears and silver claws.

In the four alabaster vessels with lids displayed further on, placed in an alabaster casket (No. 176), the entrails of the deceased Pharaoh were stored. This chest, in turn, stood inside the next exhibit – a Golden chest with a lid and statues of the goddesses-protectors of ISIS, Nephthys, Selket and Neit (# 177). In halls 7 and 8, four gilded ARKS were displayed, which were placed one in another, like a Russian nesting doll; they contained the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun.

In hall 3, which is always filled with visitors, Tutankhamun’s gold is displayed, some of which are periodically displayed abroad. When the treasure is in the In Cairo, the main attraction is the famous funeral mask with the Nemes headdress, inlaid with lapis lazuli, quartz, and obsidian.

Internal anthropomorphic coffins are decorated with the same materials, they depict a boy-king with his hands folded like those of Osiris, under the protection of the cloisonne-enameled wings of the goddesses Ouadget, Nekhbet, ISIS, and Nephthys. On the mummy of Tutankhamun (which remains in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings) were found numerous amulets, enamel ceremonial armor with inserts of glass and carnelian, breast jewelry with precious stones, and a pair of gold sandals – all this is displayed here.

The next hall of jewelry strikes the imagination. The Golden head of a VI dynasty Falcon (once attached to a copper body) from Hierakonopolis is considered the star of the collection, but it is seriously competed by the crown and necklace of Princess Khnumit, as well as the diadem and breast ornaments of Princess Sathathor. Next to the body of the latter in her tomb in Dashur, the amethyst belt and anklet of Mereret, another Princess of the XII dynasty, were found.

The ceremonial axe of yahmose commemorates the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt. The axe was found in the tomb of his mother, Queen Ahhotep. From the same cache, discovered by Mariette in 1859, comes a composite bracelet of lapis lazuli and fancy gold flies with bulging eyes – the Order of Valor, a reward for bravery.

From the time of the XXI-XXII dynasties, when Northern Egypt was ruled from the Delta, belongs exhibit # 787, displayed in hall # 2. Of the three Royal tombs excavated by Monte in 1939, the richest was the tomb of Psammetichus I, made of electra, whose coffin was discovered in the sarcophagus of Merneptah (located on the lower floor). His new Kingdom-style gold necklace is made from several rows of disc-shaped pendants.

Between hall 8 and the Atrium stand two wooden chariots discovered in the anterior chamber of Tutankhamun’s tomb. They were designed for solemn ceremonies, their gilded reliefs depicting bound Asians and Nubians. The real war chariots of the pharaohs were lighter and stronger. After completing your tour of Tutankhamun’s treasures, you can go either to the mummy Room in the West wing or to other rooms.

Mummies of the Museum

In the southern part of the second floor of the Museum there are two rooms where mummies are displayed. In hall 53 there are mummified animals and birds from various necropolises of Egypt. They show the prevalence of animalistic cults at the end of the pagan era, when their adherents embalmed everything from oxen to mice and fish.

Modern Egyptians look at these evidences of superstition of their ancestors calmly, but the exhibition of human remains offended the feelings of many of them, which led to the closure of Sadat’s famous mummy Hall (formerly room 52) in 1981. Since then, the Egyptian Museum and the Getty Institute have worked to restore the heavily damaged mummies of the kings. The results of their work are currently displayed in hall 56, where you need to buy a separate ticket to enter (70 pounds, for students-35 pounds; closes at 18: 30).

Here are eleven Royal mummies (with detailed explanations; the exhibits are arranged in chronological order, if you go around the hall counterclockwise), including the remains of some of the most famous pharaohs, in particular, the great conquerors of the XIX dynasty, SETI I and his son Ramesses II. The latter had a much less athletic build than that seen in his colossal statues in Memphis and elsewhere. There is also a mummy of Ramesses ‘ son, Merneptah, who is considered by many to be the Pharaoh of the biblical Exodus. If you don’t have a particular interest in mummies, it’s not worth paying so much to see them.

All the mummies are stored in sealed containers with controlled humidity, and most of them look very peaceful. Thutmose II and Thutmose IV appear to be asleep, and many still have hair. Queen henuttawy’s curly locks and beautiful face may indicate that She was of Nubian descent. Out of respect for the dead, excursions are not allowed here, the muted hum of visitors ‘ voices is interrupted only by periodic calls: “Please remain silent!”

The mummies were found in a Royal cache in Deir El-Bahri and in one of the rooms of the tomb of Amenhotep II, where the bodies were reburied during the reign of the XXI dynasty to protect them from robbers. To see that the mummy is empty inside, look into the right nostril of Ramesses V – from this angle you can look directly through the hole in the skull.

Other halls of the Museum

To view the rest of the exhibition in chronological order, you must start from hall 43 (above the Atrium) and move clockwise, as on the first floor. But since most visitors come here from the halls of Tutankhamun, we describe the West and East wings from this point.

Starting with the West wing, note the “Scarabs of the heart” that were placed on the throats of mummies. They were inscribed with the words of an incantation, calling on the heart of the deceased not to bear witness against him or her during the Trial of Osiris (hall 6). Among the many items from the Royal tombs of the XVIII dynasty in hall # 12 are mummies of a child and a Gazelle (display I); priests ‘ wigs and wig boxes (display L); two leopards from the hiding place of amenemhat II’s tomb (#3842) and the chariot of Thutmose IV (#4113). Hall 17 displays items from private tombs, particularly those of Sennedjem from the workers ‘ village near the Valley of the Kings.

With a skill honed on the construction of Royal tombs, Sennedjem carved for himself a stylish crypt on the door of the tomb (#215), he is depicted playing Senet. The sarcophagus of his son Khonsu depicts the lions of RUTI – the deity of the current and past day-supporting the rising sun, and Anubis embalming his body under the protection of ISIS and Nephthys.

Caskets with canopic jars and coffins are displayed in the corridor, while models from the Middle Kingdom are displayed in the inner halls. From the tomb of MeketRa in Thebes come magnificent figures and genre scenes (hall # 27): a woman carrying a jug of wine on her head (#74), peasants who catch fish with a net from reed boats (#75), cattle driven past the owner (#76). In room 32, compare the models of boats with a full crew of sailors (showcase F) with solar barges without sailors, designed to travel to eternity (showcase E). Fans of soldiers will admire the phalanxes of Nubian archers and Egyptian soldiers from the tomb of Prince Mesehti in Assiut (hall 37).

The southern wing of the Museum is best viewed by walking quickly. The middle section shows a model of the funerary complex, showing how the pyramids and their temples were connected to the Nile (hall # 48), and a leather funeral canopy of the Queen of the XXI dynasty, decorated with red-green squares arranged in a checkerboard pattern (#3848, near the Southeast staircase in hall # 50). More impressive are the two displays in the Central part: recent finds and forgotten treasures displayed near hall 54, as well as hall 43-items from the tomb of Yuyi and tuyi.

The most beautiful of these objects are the gilded Tuya mask with precious stones, their anthropomorphic coffins and statues of this married couple. As parents of Queen TIA (wife of Amenhotep III) they were buried in the Valley of the Kings, their tomb was found intact at the end of the nineteenth century. Behind the entrance to hall # 42, note the blue faience tile wall panel that comes from the memorial temple of Djoser in Saqqara (# 17).

In hall 48, near the railing of the open gallery above the Rotunda, there is a display case (No. 144) with the stone head of Akhenaten’s mother, Queen TIA, which anticipates the Amarna style, and statuettes of “dancing dwarfs” depicting Equatorial pygmies. In the same window is a magnificent, very lifelike statue of a Nubian woman (probably also Queen TIA)with a very modern-looking hairstyle.

If you come from the North wing, then the East wing opens to you in hall 14, which displays a couple of mummies and very realistic, but poorly lit Fayyum portraits found by archaeologist Flinders Petrie in Hawara. Portraits Dating back to the Roman period (100-250 years) were executed in the technique of encaustic (dyes were mixed with molten wax) from living nature, and after the death of the depicted person, they were placed on the face of his mummy.

The striking diversity of the late pagan Egyptian Pantheon is demonstrated by the statues of deities in hall 19. the Tiny figurines deserve careful inspection, especially those of the pregnant female hippopotamus-goddess Taurt (in display C), Harpocrates (Hora the child), Thoth with the head of an IBIS and the dwarf God Ptah-Sokar (all in display E), and BES, who looks almost like a Mexican deity (in display P). In display V in the center of the hall, note the image of a Choir in gold and silver, apparently used as a sarcophagus for the mummy of a Falcon.

The next room is dedicated to ostracons and papyri. Ostracons were pieces of limestone or clay potsherds on which drawings or minor inscriptions were applied. Papyrus was used for finished works of art and the recording of valuable texts.

In addition to the Book of the dead (halls 1 and 24) and the book of Amduat (which depicts the heart weighing ceremony, # 6335 in the southern part of hall # 29), please note the Satirical papyrus (#232 in display 9 on the North side), which depicts cats serving mice. In the images created in the Hyksos period, cats represent the Egyptians, and mice represent their rulers, who came from countries that were formerly part of the Egyptian Empire.

The image suggests that the rule of foreigners in Egypt was perceived as unnatural. The scribe’s writing apparatus and the artist’s paints and brushes (near the door at the other end) are also displayed in hall 29. In the next hall No. 34 there are musical instruments and statuettes of people playing them.

In the corridor (hall 33) there are two interesting armchairs: a seat from the Amarna toilet is displayed in the “O” window near the door, and in the “S” window there is a birthing chair, very similar to what is used in our time. Hall 39 displays glass products, mosaics and statuettes from the Greco-Roman period, while hall 44 displays Mesopotamian faience wall coverings from the palaces of Ramesses II and III.