The ancient inhabitants of Deir el Medina were writers, painters, draftsmen, sculptors and stonemasons, humble servants of the divine endeavors of the pharaohs. For the Pharaohs of the 19th and 20th Dynasty (1295-1069 BC), the Ramesses (I to XI) and Setis, they carved out the royal tombs in the rocks of Thebes (now Luxor). The mighty temples of Luxor and Karnak were a few miles away.

They had a regular life. A week of work, two days at home. On average, they worked on a grave for six years. They did not just do that at their own artistic discretion. They were employed by a royal institution called ‘The Grave’. The Tomb (the Great and Venerable Tomb of the Pharaoh’s millions of years, life, health, strength, in the west of Thebes) was a bureaucratic organ that suffered from compulsion to control. She wrote down everything on pottery (in the draft) and on papyrus (in the net): work schedules, deliveries, absences and the apologies invoked (temple service, painful periods), disputes, irregularities, claims and delays, correspondence, official reports and sentences . Pharaoh himself, through his visor, kept a close eye on the work. The afterlife was not just anything for the Egyptians, but very important.

years. They did not just do that at their own artistic discretion. They were employed by a royal institution called ‘The Grave’. The Tomb (the Great and Venerable Tomb of the Pharaoh’s millions of years, life, health, strength, in the west of Thebes) was a bureaucratic organ that suffered from compulsion to control. She wrote down everything on pottery (in the draft) and on papyrus (in the net): work schedules, deliveries, absences and the apologies invoked (temple service, painful periods), disputes, irregularities, claims and delays, correspondence, official reports and sentences . Pharaoh himself, through his visor, kept a close eye on the work. The afterlife was not just anything for the Egyptians, but very important.

The craftsmen were paid in kind, with grain, vegetables, fish, and linen, and were well supplied with wood, water, vases, and utensils. Gatekeepers and soldiers guarded the village and the necropolis. A judge resolved any issues so that nothing prevented them from concentrating on their work. The complex and mysterious magic that the pharaohs wrought around their cult of the afterlife was highlighted from the point of view of the ordinary working person. The anonymous ancient Egyptian suddenly becomes an individual with a name, face and family. Its seats, mirrors, spoons, chisels and necklaces are identical to ours. Stripped of its magical haze, ancient Egypt becomes astonishingly contemporary, and that is precisely why so extraordinary.

It becomes all the more interesting because that ordinary person turns out to be a learned writer, a delicate painter and skilled sculptor. In the limestone doorposts and sills they carved scenes of their ancestor worship and representations of gods, they carved busts and steles which they put in small chapels, and prepared their own tombs with great care.

All those unpillared tombs yielded a wealth of objects, domestic objects whose wear shows they have been used for a lifetime, and funerary art to accompany the deceased. They practiced their handwriting and language by copying and varying passages from classical works. On limestone fragments they made sketches in red and black ink, experiments that they threw away and on which they could let their imaginations run wild. In the light of eternity, they are trivial, and that is why they are so fascinating.

They show what could never be addressed in the official world: a mother breastfeeding her child, the portrait of a toiling stonemason, people dancing and music, erotic scenes, delightful satires and animal fables. A mouse of high rank is served by a mischievous looking cat and is served a roast goose while delicately smelling the lotus flower. The inverted beast world is a double parody of the stereotypical sacrificial scenes that adorn the walls of the tombs. The Egyptians could laugh at death. The small animal scene breathes more life into the Egyptian world than rooms full of sophisticated burial scenes can.

From the thousands of text fragments and objects excavated in Deir el Medina, some individuals also emerge clearly. That too is exceptional for the rigid collective Egyptian society. To the pharaohs, the artists were anonymous craftsmen who humbly worked in the service of the cult governed by above.

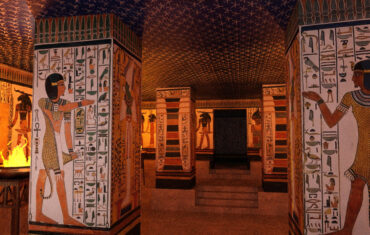

Tomb of Pashedu

The finds from Deir el Medina have contributed in a unique way to our knowledge of the religious life in Egypt. While the village and its people were only a few kilometers from the great shrines of the official pantheon and the kingdom gods, it is in Deir el Medina that we get to know all kinds of unknown aspects of the folk belief, with its expressions of personal devotion. This tells us how many testimonies must have been lost elsewhere, preserved here by historical accident. Undoubtedly, local deities throughout the Nile Valley have played an important role in everyday religious life.

A number of stelae have been found in Deir el Medina, including those dedicated to Nefertari, on which ears are chiseled, while separate pairs of stone ears were placed as votive objects near chapels. This practice had already been sporadically established elsewhere, but nowhere were so many examples found as here. The ears served to make the gods listen even better to the prayers of the believer. (Sandwiches with ears have been found in the graves themselves). On the Oren stele of Iern-ioetef are engraved four large ears that illustrate the text next to it, in which the queen is referred to as “she who listens to the prayers”.